Our Vision

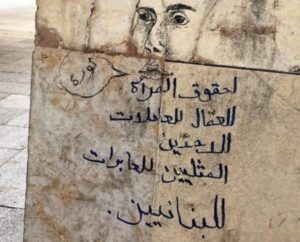

Proud Lebanon’s vision is to reach a world where there is no violence, discrimination or violations of human rights, where all people live equally in dignity, freedom and inner peace.

Our Vision

Proud Lebanon’s vision is to reach a world where there is no violence, discrimination or violations of human rights, where all people live equally in dignity, freedom and inner peace.

Our Mission

Proud Lebanon aims to empower people who suffer from discrimination.

We are dedicated to promote tolerance in Lebanon and the region, where people are effectively empowered and to ensure the well-being of individuals.

Main goals:

With the aim of fully integrating the LGBTIQ+ community in the society and providing access to equal rights, Proud Lebanon provides awareness-raising sessions to LGBTIQ+ individuals, legal and psychological support, capacity-building workshops to various professionals (including journalists, lawyers, social workers, educators and others).

Earlier, with the aim of addressing the needs of vulnerable Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transsexual (LGBT) people in Lebanon and helping them advocate for their rights, Proud Lebanon provided empowerment workshops, training of stakeholders and advocacy to raise awareness in Lebanese society on issues of LGBT concern took place.

Starting from August 2017, Proud Lebanon began implementing new projects, which seeks to provide various services to vulnerable individuals to detainees across the country.

Through these projects, Proud Lebanon provides legal assistance and counseling in the detention places, recreational activities for the detainees, awareness raising activities for the detainees, psychological and medical support for individuals who have been recently released.

Additionally, as part of its work, Proud Lebanon hosts support group activities for people living with HIV (PLWH). Proud Lebanon is working on providing them with a safe space that will help them reintegrate in the wider society. Effectively empowered, these individuals have founded Support+ within Proud Lebanon, the only openly HIV positive advocacy group in Lebanon, to advocate for the rights of the PLWH (people living with HIV) within the LGBTIQ+ community, spread knowledge about the issue and provide support to newly diagnosed individuals.

If you are in need of any support, do not hesitate contacting us on our Hotline

Since the beginning of the armed conflict in Syria in 2011, Lebanon has been in the spotlight as one of the worst humanitarian crisis unfolded. The influx of refugees from Syria caught the attention of almost every media outlet in Lebanon and the world.

As of 31 July 2018, according to the UNHCR, there are 976,002 registered Syrian refugees (estimated to be 1.5 million including the unregistered refugees), approximately 280,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, 32,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria, 150,000 – 200,000 migrant workers, and approximately 60,000 stateless individuals of Lebanese origin. The gravity of the situation is evident if we compare these numbers to the number of Lebanese individuals (approx. 4,1 million).

However, the people living in Lebanon face many other issues which are not always related to them being refugees.

For example, even though Lebanon has signed and ratified both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), these accessions are not enough to guarantee the respect of human rights in Lebanon. There is no transposition of the provisions enshrined in these treaties into the domestic law, which are rarely respected.

Multiple violations of human rights are reported in Lebanon, such as torture, ill-treatment, arbitrary detention and very poor prison conditions. On several occasions, the State has failed in its obligation to submit reports to the various bodies in charge of monitoring the effective implementation of international instruments such as the Human Rights Committee for the ICCPR or the Committee against Torture for the Convention against Torture.

Issues faced by LGBTIQ+ individuals in Lebanon

Issues faced by LGBTIQ+ individuals in Lebanon

The members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Questioning (LGBTIQ+) community in Lebanon are particularly vulnerable as they lack protection support and face discrimination on the grounds of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity (SOGIE).

These individuals can be legally prosecuted for consensual homosexual relations between adults, according to article 534 of the Criminal code of Lebanon, which reads: “any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punishable by imprisonment for up to one year”. The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBTIQ+ community in Lebanon.

As a practical matter, enforcement of the law is varied and often occurs through occasional police arrests.

While Lebanon remains far from an LGBTIQ+-friendly country, activists have been able to log a few wins. In particular, four landmark rulings in 2009, 2014, 2016, 2017 and in March 2019, set important legal precedents in the fight to abolish Article 534. The judges in these cases acquitted defendants charged under 534, arguing that conceptions of nature are socio-cultural constructs, making it impossible to designate any behavior categorically unnatural. The LGBTIQ+ community is present in all regions of Lebanon (such as North Lebanon: Tripoli, East Lebanon: Zahle), but because of fear of arrest, and other safety related risks, they tend to stay out of sight and without any support from NGOs since most of these organizations work primarily in Beirut.

As noted in “The LGBTIQ+ community in Lebanon, documenting stories of torture & abuse” report by Proud Lebanon, LGBTIQ+ individuals suffer more from psychological disorders than heterosexual individuals (Kuyper & Fokema, 2011).[1]

In addition to above mentioned, LGBTIQ+ individuals face discrimination whilst seeking sexual health examinations and treatment. As a result, in a report published in 2016 the National AIDS Program (NAP) reports that out of 5000 individuals participating in a UN monitored study, 27.5% of men having sex with men (MSM) were HIV positive, while in the 2015, the National AIDS Program (NAP) reported 113 new cases of HIV/AIDS Lebanon. 86% of them were MSM (males having sex with males) individuals[2]. The LGBTIQ+ community is one of the most vulnerable groups at risk of infectious sexual diseases in Lebanon, as many are too afraid to go for a test or seek treatment for HIV or other STIs because of the discrimination they might face, a fear of disclosure to an employer or family, and a lack of awareness of safer sex or even due to financial obstacles.

Proud Lebanon is one of the NAP’s partners and provides Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) tests, and was the first organisation to host Support+ an HIV support group dedicated for youth in the LGBTIQ+ community.

Proud Lebanon provides follow up through Support+ to the newly diagnosed HIV individuals and although the HIV rapid testing and medication are available and provided for free by the NAP, patients have to pay for viral load and CD4 tests every 6 months as well as the medical check-ups undergone by the Infectious diseases specialists (IDS). Therefore, individuals with low income and refugees cannot access vital screening test to see if they are responding to antiretroviral therapy (ART) – an essential need for those living with HIV as well as to follow up with specialists.

Access to various services to some of the most vulnerable groups is limited and often quite expensive and/or inaccessible. This includes access to specialised treatment for people living with HIV, access to medical support for people with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), access to Psycho-medical and other services for LGBTIQ+ individuals, etc. Finally, the public’s knowledge on issues related to LGBTIQ+ rights, STIs, HIV and other issues is not sufficient and often leads to stigmatization and discrimination against these populations.

As outlined in a needs assessment conducted by Proud Lebanon, LGBTIQ+ individuals in Lebanon still have very limited access to medical, legal and psychological support as only 9% of interviewees stated that they have been provided with legal support (even though more than 80% stated that they need it).[3]

Issues faced in Lebanese prisons

Issues faced in Lebanese prisons

The prisons in Lebanon are a disgrace and dark record of the country in the field of human rights. They are managed by the Ministry of Interior and in many cases with limited resources. The current situation is such that the prisons are packed to twice their capacity; the actual capacity of Lebanon’s prisons is around 3,600 inmates, currently detaining more than 6939 prisoners.[4] Prison and detention center conditions are harsh, and prisoners often lack access to basic sanitation. In some prisons, such as the central prison in Roumieh, conditions can be considered as life threatening. Facilities are not adequately equipped for persons with disabilities.

The prisoners are detained in cruel and inhumane conditions. A number of inmates include cases of arbitrary detention, detained for excessive periods of time pending trial. Numerous illegal migrants, asylum seekers and refugees often spend months languishing in cells past their release due date. On top of all these conditions, there are many reported cases of death, use of torture and ill-treatment in the prisons. [5]

The Lebanese Government is failing in its obligations and its responsibility to find an adequate solution to the above-mentioned problems and to improve the detention conditions in prisons. The Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights which is supposed to have a monitoring role and legislative is failing to turn up for work and to make an effective approach to the issue of prisons despite the fact that from time to time members of the Committee visit a number of Lebanese prisons.

[1] “The LGBTIQ+ community in Lebanon, documenting stories of torture & abuse”, Proud Lebanon (Annex 1)

[2] HIV and SRH linkages infographic snapshot – NAP, UNAIDS, WHO, UNFPA, et al.; Available at: http://bit.ly/2wF2rQR

[3] “Needs Assessment Report” for Stand Up project, Proud Lebanon (Annex 2)

[4] Ministry of Justice’s website: https://goo.gl/8RWj5P

[5] BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR – 2016 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Report – March 3, 2017